Search -

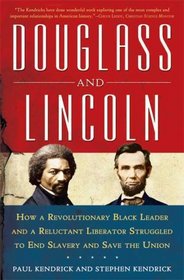

Douglass and Lincoln: How a Revolutionary Black Leader and a Reluctant Liberator Struggled to End Slavery and Save the Uni

Douglass and Lincoln How a Revolutionary Black Leader and a Reluctant Liberator Struggled to End Slavery and Save the Uni

Author:

The influence Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln had on each other and on the nation altered the course of slavery and the outcome of the Civil War. Although Abraham Lincoln deeply opposed the existence of slavery, he saw his mission throughout much of the Civil War as preserving the U nion, with or without slavery. Frederick Douglass... more »

Author:

The influence Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln had on each other and on the nation altered the course of slavery and the outcome of the Civil War. Although Abraham Lincoln deeply opposed the existence of slavery, he saw his mission throughout much of the Civil War as preserving the U nion, with or without slavery. Frederick Douglass... more »

ISBN-13: 9780802716859

ISBN-10: 0802716857

Publication Date: 12/23/2008

Pages: 320

Edition: Reprint

Rating: ?

ISBN-10: 0802716857

Publication Date: 12/23/2008

Pages: 320

Edition: Reprint

Rating: ?

0 stars, based on 0 rating

Genres:

- Biographies & Memoirs >> Community & Culture >> Black & African American

- Biographies & Memoirs >> Historical >> General

- Biographies & Memoirs >> Historical >> United States >> General

- Biographies & Memoirs >> Historical >> United States >> Civil War >> General

- Biographies & Memoirs >> Leaders & Notable People >> Presidents & Heads of State

- Biographies & Memoirs >> Leaders & Notable People >> Military >> American Civil War

- History >> Americas >> United States >> Civil War >> General

- History >> Americas >> United States >> General

- Nonfiction >> Social Sciences >> Sociology >> General