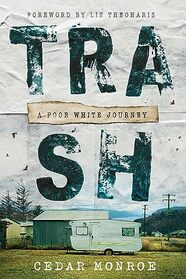

Cedar Monroe's indictment of the systemic mistreatment of the poor white population of America comes off as part biography, part polemic, part pie-in-the-sky and winds up serving none of the topics well.

The statistics quoted are staggering. "Some 140 million people in this country" Monroe tells us, "are poor." Many of them are homeless. All are underserved by the social agencies designed to assist them, are dependent on food stamps to survive, are poorly served or denied service by medical providers, are ignored or neglected by public schools, and are routinely brutalized by the law enforcement and court systems.

The two villains who loom largest in this state of affairs, Monroe asserts, are the doctrine of private property ownership and the financial model of capitalism (which is where a lot of readers will get off the bus). Private property ownership, whether of residences or land itself, means that dispossessed people have literally no "where" to go when squeezed between rising housing costs and the disappearance of family-wage jobs for those without specialized skills. And capitalism is the cause of many of these woes because it depends on a large pool of surplus labor which can be called upon when needed to do unskilled and dangerous work for very little pay and then discarded when the need for them ends. Therefore, the individuals and organizations who benefit most from the system are also largely responsible for undercutting any large-scale programs that would deplete that impounded labor pool.

One of the long-term solutions, Monroe suggests, is convincing the poor white population to cross racial and class lines to join forces with communities of color, of immigrants, of LGTBQ+ people, and join forces with national groups like the Poor People's Campaign in order to multiply their political clout and force their way into a place at the table. No concrete suggestions are made about how to overcome generations of poor white rage at communities of color, or of how to smack down the White Supremacist outlook so prevalent within the poor white community. Nor is there any acknowledgement that political power of the people does not and cannot break the stranglehold the one-percenters have on the wealth and the means of wealth production in America.

On the micro level, Monroe looks at work done in the homeless communities of Grays Harbor County in Washington State. And after years of struggling to provide food, medical care, substance abuse treatment options, and intervention in mental health crises, Monroe's group, Chaplains on the Harbor, sought a solution through the purchase of 22 acres of pastureland on which to raise truck-garden produce and provide living space and job training for members of the homeless community. After raging against the ills of private property for 200 pages, Monroe barely acknowledges the irony of this admittedly stopgap solution.

No one with any grasp of America's ills can deny that the growing percentage of have-nots in our society pose a potentially fatal threat to our social, political, and economic structure, or that finding resolution to the problems must begin with honestly and squarely looking at the causes and extent of the problem. Monroe's work gamely attempts to do just that, but it falls woefully short of the goal.

The statistics quoted are staggering. "Some 140 million people in this country" Monroe tells us, "are poor." Many of them are homeless. All are underserved by the social agencies designed to assist them, are dependent on food stamps to survive, are poorly served or denied service by medical providers, are ignored or neglected by public schools, and are routinely brutalized by the law enforcement and court systems.

The two villains who loom largest in this state of affairs, Monroe asserts, are the doctrine of private property ownership and the financial model of capitalism (which is where a lot of readers will get off the bus). Private property ownership, whether of residences or land itself, means that dispossessed people have literally no "where" to go when squeezed between rising housing costs and the disappearance of family-wage jobs for those without specialized skills. And capitalism is the cause of many of these woes because it depends on a large pool of surplus labor which can be called upon when needed to do unskilled and dangerous work for very little pay and then discarded when the need for them ends. Therefore, the individuals and organizations who benefit most from the system are also largely responsible for undercutting any large-scale programs that would deplete that impounded labor pool.

One of the long-term solutions, Monroe suggests, is convincing the poor white population to cross racial and class lines to join forces with communities of color, of immigrants, of LGTBQ+ people, and join forces with national groups like the Poor People's Campaign in order to multiply their political clout and force their way into a place at the table. No concrete suggestions are made about how to overcome generations of poor white rage at communities of color, or of how to smack down the White Supremacist outlook so prevalent within the poor white community. Nor is there any acknowledgement that political power of the people does not and cannot break the stranglehold the one-percenters have on the wealth and the means of wealth production in America.

On the micro level, Monroe looks at work done in the homeless communities of Grays Harbor County in Washington State. And after years of struggling to provide food, medical care, substance abuse treatment options, and intervention in mental health crises, Monroe's group, Chaplains on the Harbor, sought a solution through the purchase of 22 acres of pastureland on which to raise truck-garden produce and provide living space and job training for members of the homeless community. After raging against the ills of private property for 200 pages, Monroe barely acknowledges the irony of this admittedly stopgap solution.

No one with any grasp of America's ills can deny that the growing percentage of have-nots in our society pose a potentially fatal threat to our social, political, and economic structure, or that finding resolution to the problems must begin with honestly and squarely looking at the causes and extent of the problem. Monroe's work gamely attempts to do just that, but it falls woefully short of the goal.